Peter and I have been updating the Tandem Exchange site translations over the past few weeks, and are now able to announce support for Arabic, Japanese, Korean, Simplified Chinese, and Traditional Chinese as first-class UI languages on the website in addition to the original German, Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Russian translations that we did first.

There was a moment on Monday when I let slip that the website was starting to take on the feel of a “real” website, and that is true. We now have 12 full translations of the website, which Google can grok for each of its region-specific search indices, and which we can serve to a wide swath of users around the world.

One of the weirder things about multiple-language support learned along the way, is the way the HTTP Accept-Language header formats a user’s UI language preference vs. the way GNU gettext specifies the same information vs. the way the Unicode Consortium specifies the same information vs. the way Facebook, Google, and Twitter specify the same information. And then how Django chooses to use that information when setting the site’s presentation language and looking up the correct gettext catalogs.

HTTP

The HTTP Accept-Language header usually looks something like: “Accept-Language:en-US,en;q=0.8” where the language codes are specified by a massive, long-winded standard called BCP47. The standard defines a language code to look something like en-US or zh-CN or zh-TW, but the standard doesn’t really bother giving a list of common language codes, leaving that instead to the combinatorial explosion that results by mixing together one entry from each of the categories of the IANA Subtag Registry.

Django

In the Django settings.py file, you specify the list of languages that the website is supposed to support, and you do this using language-code strings that look like this, where the first entry in the tuple looks roughly like BCP47:

LANGUAGES = (

('ar', 'العربية'),

('de', 'Deutsch'),

('en', 'English'),

('es', 'Español'),

('fr', 'Français'),

('it', 'italiano'),

('ja', '日本語'),

('ko', '한국어'),

('pt', 'português'),

('ru', 'ру́сский'),

('zh-cn', '简体中文'),

('zh-tw', '繁體中文'),

)

Note, however, that the language-code is strictly lowercase and uses a hyphen as a separator.

gettext

When building the translation catalogs for Django, you have to use gettext’s locale-naming format, which looks something like en_US or zh_CN.

So when you’re looking at your app’s locale/ subfolder, it will end up containing directories looking something like:

$ ls locale ar de en es fr it ja ko pt ru zh_CN zh_TW

Note the difference in the separator (hyphens vs. underscores) and the region code (lower vs. upper case). On a case-sensitive filesystem, you have to get this exactly right.

Unicode Consortium CLDR

But let’s say you’re also using the Unicode Consortium’s Common Locale Data Repository to generate some information instead of having to write it all out yourself? They use a slightly different set of language/region/locale identifiers, which are generally sensible but in the case of the Chinese languages, use zh_Hans and zh_Hant as parts of the filenames and language identifiers:

ee_TG.xml fr_CF.xml kw_GB.xml sah_RU.xml yo.xml ee.xml fr_CG.xml kw.xml sah.xml zh_Hans_CN.xml el_CY.xml fr_CH.xml ky_KG.xml saq_KE.xml zh_Hans_HK.xml el_GR.xml fr_CI.xml ky.xml saq.xml zh_Hans_MO.xml el.xml fr_CM.xml lag_TZ.xml sbp_TZ.xml zh_Hans_SG.xml en_150.xml fr_DJ.xml lag.xml sbp.xml zh_Hans.xml en_AG.xml fr_DZ.xml lg_UG.xml se_FI.xml zh_Hant_HK.xml en_AS.xml fr_FR.xml lg.xml seh_MZ.xml zh_Hant_MO.xml en_AU.xml fr_GA.xml ln_AO.xml seh.xml zh_Hant_TW.xml en_BB.xml fr_GF.xml ln_CD.xml se_NO.xml zh_Hant.xml en_BE.xml fr_GN.xml ln_CF.xml ses_ML.xml zh.xml en_BM.xml fr_GP.xml ln_CG.xml ses.xml zh.xml~ en_BS.xml fr_GQ.xml ln.xml se.xml zu.xml en_BW.xml fr_HT.xml lo_LA.xml sg_CF.xml zu_ZA.xml en_BZ.xml fr_KM.xml lo.xml sg.xml

Facebook passes back the locale of their users like so: ar_AR, zh_CN, zh_TW, and there’s a list of their supported languages and locales here. Of the bunch, they’re the most consistent, sticking to a [2-letter language code + 2-letter ISO country name] combo.

Google passes back the locale of their users like so: ar, zh-CN, zh-TW, and there’s a list of their supported languages and locales here. They mix and match pure 2-letter language codes with [2-letter language code + 2-letter ISO country name] and even [2-letter language code + 3-letter ISO region code] combos. Sigh.

Twitter generally passes back the locale of their users using 2-letter language codes such as ar, de, en, etc., but for Chinese they pass back zh-cn and zh-tw for Simplified and Traditional Chinese. Of course, this is pure speculation, because the most detailed available info about this comes by reading the source of their Tweet button generator.

So…

Needless to say, it all gets a bit confusing. But the point is this:

- In the Django settings.LANGUAGES list, strip down your language codes to 2-letters if possible, use all-lowercase, and hyphens to separate a [language code – region code] identifier, or Django will complain.

- On disk, make sure your translation files are in directories like locale/en, locale/zh_CN, and so on, with underscores and capital letter region codes where necessary.

- And if you’re ever using OAuth to authenticate your incoming users, make sure to process the locale information coming from Facebook, Google, or Twitter, into the lower-case, hyphen-separated form used by Django, before you write it into the user’s profile.

One Final Thing

It was definitely interesting to see what kind of changes to the styling and layout were necessary to support the Arabic language. One of the tricky things about making sure things style properly in right-to-left mode is the fact that CSS float: property and text-align: property do not take on opposite meanings when you set the text-direction in the body content.

So in our case, we had a panel that relied on floats to style properly.

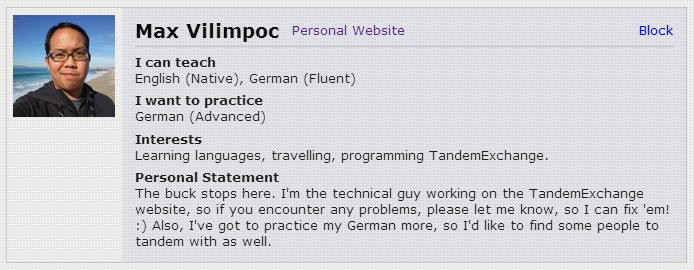

In the left-to-right case, it looks like:

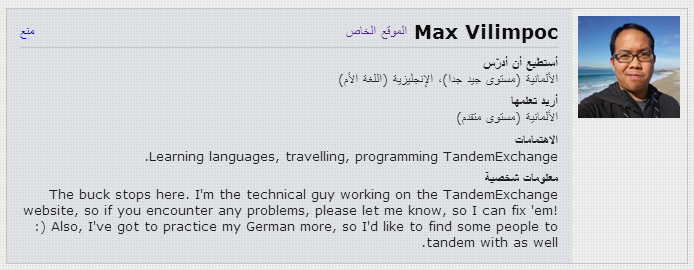

In the right-to-left case, it looks like:

To get it to do this, we had to add a {% if LANGUAGE_BIDI %}rtl{% endif %} rule to each of the CSS classes that needed the explicit float: property change, then specify those styles like so:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

|

.name {

float: left;

text-align: left;

}

.name.rtl {

float: right;

text-align: right;

}

|

And that’s it, for now.