I’ve been thinking about how to reduce the trail of information I leave behind while surfing the web.

When the web was first invented, it was, by definition, a stateless place. There was no read/write web, PHP was still a glimmer in its inventors’ eyes, and dynamically-generated content was still the domain of those hardy Perl hackers who could stand writing code for ~/cgi-bin. Things were far less interactive. You browsed to websites, and those websites recorded some minimal information about you to their log files: your Internet Protocol address, what browser you were using (via the User Agent header), essentially just information that was part of the protocol.

In the mid-1990s, Bell Labs and Netscape introduced the cookie specification for the purpose of enabling web commerce, with the unintended consequence of transforming the entire web into a highly stateful place. (Ok, the RFC states the reverse, but we all know what really happened.) Now all of your previous interactions with a website could be in some way encoded, preserved, and recalled via the magic of a browser cookie, even by unintended websites that you may just have brushed up against like so much poison ivy. The ease with which third parties have been tracking our online behaviors, of course, has never been the same.

To reduce one’s web footprint, common tricks were applied: Using Ad- and Flash-blocker plugins in Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox was one, using an /etc/hosts file was another.

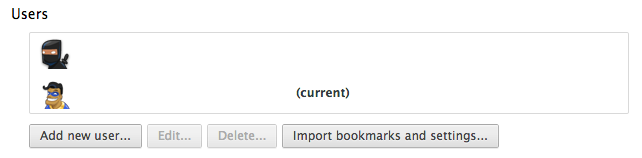

These were things I’d already tried. But with the newer versions of Chrome, I’d begun to use multiple user profiles to specifically separate the profiles that I presented to online services. I had a profile for Facebook, a profile for Google Docs and Analytics, one for my web development work, and so on. The user credentials, cookies, and tracking data in each profile were kept entirely separate from one another, perhaps giving some websites the impression that I was several different people. It was all a bit tedious and, actually, sub-optimal.

I realized:

The more natural usage-pattern split is between stateful and stateless browsing habits.

In other words:

- If I must be logged in to interact meaningfully with a website, to ensure that it knows who I am or to maintain a shopping cart full of goods, that’s a stateful transaction.

- If I don’t need to be logged in to receive information from a website, because it doesn’t need to care about who I am or keep track of an order I’ve placed, that’s a stateless transaction.

Examples:

| Stateful browsing |

(example) |

Stateless browsing |

| Webmail |

(Gmail) |

Plain old web browsing, even using Google Search, can be a stateless affair.

No more ads showing up on partnering display networks immediately after you've googled something!

Any kind of browsing where your actions on a webserver are read-only can be stateless. |

| Social Networks |

(Facebook) |

|

| Shopping |

(Amazon, eBay) |

|

| Source repositories |

(github) |

|

| Bugtracking Services |

(Redmine) |

|

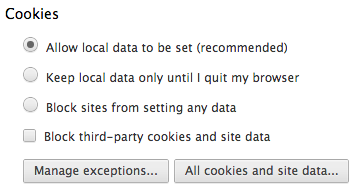

There are a handful of websites I use regularly that need cookies to function properly: Tandem Exchange, the issue tracking system for Tandem Exchange, Google AdWords, Google Analytics, Google Docs, Facebook, Twitter, Odnoklassniki, VKontakte, and a range of other social networks I use to test social login capabilities. These sites have a legitimate need for cookies, since without them, I can’t prove my identity and access rights.

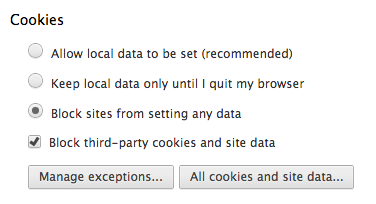

For everything else, I go stateless.

It turns out, actually, that you can turn cookies off completely for any kind of web browsing where you’re just reading something or looking something up. Unless it’s behind a paywall, or some other access control mechanism, plain web surfing does not require cookies, and may even be better that way (since the website can’t suggest more crap for you to look at, based upon the things it thinks you like). All of your requests must be interpreted as neutral requests. The sort of tuning, customization, filtering, and presentation of the web to your exact preferences and prejudices, can not happen, since each request has to be treated impartially.

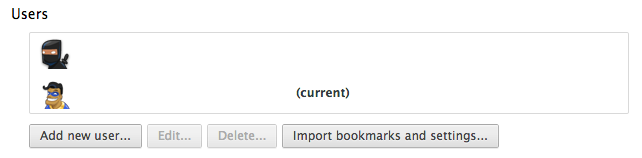

So that’s what I’ve done. I’ve created one user profile, in which all the cookies and nasty bits of tracking can occur; and I’ve created a second user profile, in which I accept absolutely none of it. Another way to think about it is that I have a profile that I explicitly allow everyone to know everything about, and I have a profile that no one knows anything about. Whenever I’m required to log into a web service, I use the first profile. Whenever I just want to look something up and browse anonymously (which is 99% of the time), I use the second profile.

Keep in mind, also, that Incognito Mode on Chrome still accepts cookies from all sources. So you may think you’re not being followed around, but you still will be.

Settings (in Chrome)

Create two user profiles via the Settings page:

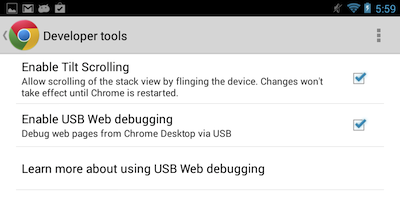

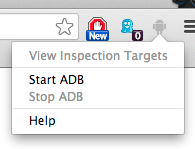

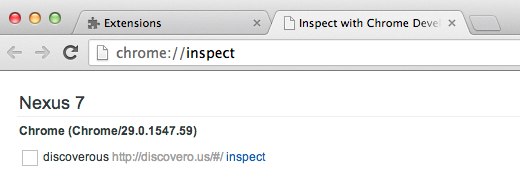

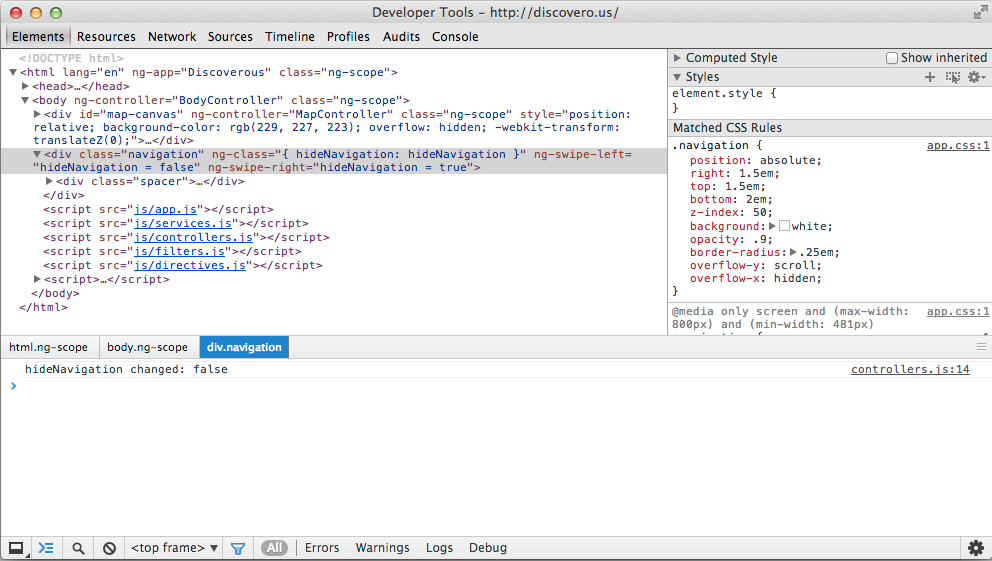

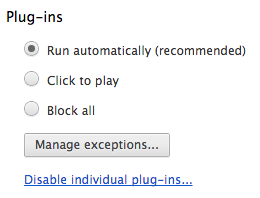

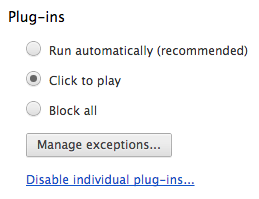

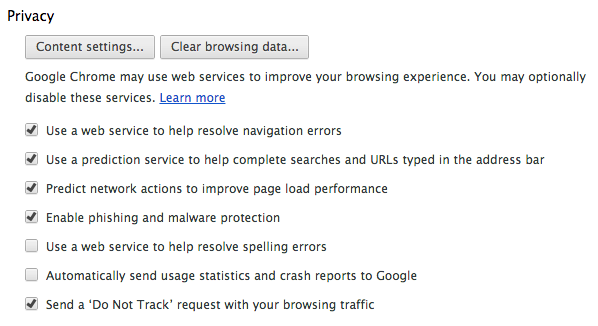

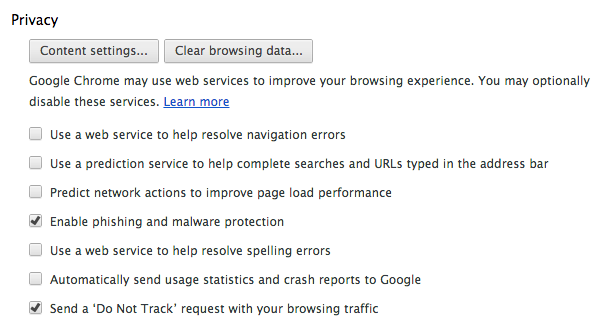

Then just set the profile settings as follows, and use the profiles as appropriate.