tl;dr

Event organization: A, Food: A, Swag: A+, Technical Ease of Use: A, Usefulness In The Real World: B?

The Long Story

Over the past 2 months, I started attending my first hackathons, gaining exposure to a number of new technologies, and getting a view into the whole culture of these events.

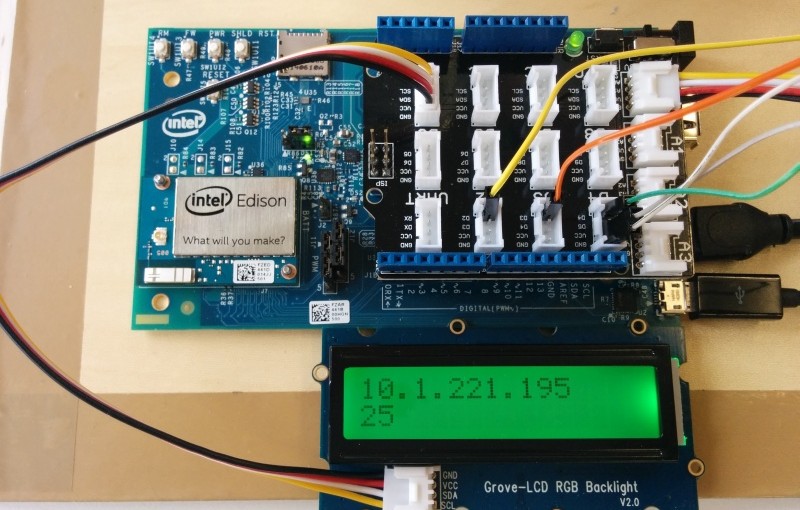

This is the retrospective of the first hackathon I attended. Sponsored by Intel, the hackathon revolved around finding uses for their Edison embedded development platform. I’d been reading about the device for some time, and signed up pretty far in advance of the event to some of their mailing lists. So when their roadshow came to town, I decided to make some time to check it out.

The event itself took place at Betahaus, one of the better-known coworking spaces in Berlin. Intel took over two floors on the last weekend in April. The first 100 people through the door were slated to receive the development kit, and a bag of sensors, and also have access to additional sensors that might be useful for their projects. Intel had staff on hand to answer questions, and a handful of devs who could answer deeper questions.

There was an opening ceremony, which dragged on for a bit too long. There was an explanatory session, teaching people how to set the board up, after the unboxing.

Then, they cut us loose to build whatever we wanted to build.

I have to admit here that I was pretty skeptical of the dev kit’s completeness and ease of use, but I have to say here that I was pleasantly surprised about my incorrect assumption. It turns out, actually, that the setup time on the Edison compares favorably and in some places improves on that of the setup of the Raspberry Pi, for embedded use scenarios.

Board bring up requires less from you, as a user, than with an RPi.

Here’s why: The Edison board includes flash memory (with a ready-to-boot copy of Yocto Linux on board), WiFi and Bluetooth on board, and an FTDI RS232 serial to USB converter on board. The importance of being able to plug right into a serial console cannot be overstated for embedded dev. And the whole thing can be powered directly from a USB port on your laptop, w/o any concern that it draws too much amperage. Pricewise, adding WiFi and Bluetooth, and buying a level-shifter for RS232 already makes a RPi more expensive.

All in all, the bring up time, for me, was less than 5 minutes.

The sensor baggie that we received from Intel (since they knew people probably wouldn’t have a lot of sensors with them) included different modules with standardized connectors for an Arduino-compatible breakout board, such as: light sensor, moisture, vibration, gas, LEDs, accelerometers, sound, water flow, buttons, buzzers, and a capacitive touch sensor.

I would estimate the total cost per attendee to be somewhere in the neighborhood of $250, maybe more. Intel put a lot of capital into this, and it showed.

Support for the sensors was pretty good, in C, Javascript, and Python, though there were some sensors that hadn’t been covered yet. But it wasn’t nearly as many as I had expected. Later updates to the board support package (opkg upgrade) pulled in support for these devices, though.

There were no real tasks assigned and no major constraints placed on the hackathon, just hack away on something using the Edison, that was all. (This, I found out over the next few weeks, was not so much the case with some other hackathons.)

In any case, the supporting factor to the event, and which made it very enjoyable: Fantastic food. Seriously, they did not spare a cent to keep the devs happy, and we spent a good 24 hours munching on sushi, burgers, and pizza. And, of course, beer. No one went hungry. This may seem like a petty point, but it kind of is not. For anyone seeking to get the best out of the people attending their event, you’ve got to put good food on the table.

Otherwise, we will leave your event and go get better food and spend less time with the software API or technology that you’re trying to push. (This happened elsewhere.)

As far as usefulness goes, I’ve actually taken the Edison dev kit to two other hackathons, but have not replicated the third-place win I received at the Intel hackathon. It’s been useful, and used, to do a few other things now, but I’m still trying to figure out the ideal setting for the hardware. Also, it wasn’t quite clear how well Edison would hold up under battery-powered operation for the long haul. Being that it’s a quite powerful processor, I still haven’t run the full range of qualification tests to see how well it stacks up against RPi or Arduino on the power-consumption front.

I can say I’m interested to see what happens when the Curie embedded module comes out, and what happens when the move to the 14nm or 10nm process nodes happens. I’ve also always been quite skeptical about the smart-this and connected-that world that has been promoted so heavily, I think an IoT world is a world running a lot of out-of-date software, and I definitely know that there are very few use cases that people have pointed to that really make brilliant use of the technology. But having the hardware available still makes all kinds of things possible that weren’t even on the drawing table previously, so that’s good.

So that’s it, the first hackathon set a high standard for the rest to try to live up to. (I’ll detail how well they did in future posts.)